Book Musings: The Righteous Mind - Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion

Reflections on the book, The Righteous Mind, by Jonathan Haidt. (Don’t be frightened by the word Righteous in the title: this is not about religion!)

I just finished a book that is now on my top 5 books of all time list. Maybe top 3. (Time will tell.) In my wildest fantasy, I would strap every human into a chair, pull their eyelids open with a terrifying machine and force to them read it.

I just finished a book that is now on my top 5 books of all time list. Maybe top 3. (Time will tell.) In my wildest fantasy, I would strap every human into a chair, pull their eyelids open with a terrifying machine and force to them read it.

This book basically reinforces with (what I find to be) very good arguments, a message that I’ve been trying to articulate and spread for a long time. It has to do with how we relate to those with radically different worldviews, politics, religions (or lack thereof), etc. Like many in my generation and after, I’m a child of two ideological worlds. I was raised in a conservative, evangelical Christian subculture. Most of my world revolved around a church of people with with a very homogenous worldview. Everybody read the same evangelical Christian books, listened to the same evangelical Christian music, voted Republican, and in general viewed the “secular world” as evil. We thought most colleges were dens of atheists whose primary goal was turning our innocent youth into evolution-believing democrats. (Well… I guess I still think that part’s probably true.) We were the ones yelling that Cabbage Patch Kids and Smurfs were satanic because there were middle eastern names associated with them, and that Tinky-Winky from the Teletubbies was an example of the “homosexual agenda” attempting to normalize deviant behavior.

But my trajectory was a bit off from that sub-culture because my parents are intellectuals who love science, literature, science fiction and fantasy. I don’t think they ever bought into the hysteria regarding demons hiding behind every bush. And they had no fear of intellectuals, philosophy and science.

So that’s my origin milieu. But besides smart, creative parents, I’ve had quite a few other influences that have pushed me in a more liberal direction. Being an Air Force brat I’ve lived all over the world, and all my adult life I’ve lived in very liberal areas. I work in the very liberal, creative entertainment industry. The end result being a very mixed heart. Perhaps this is why I’m oriented toward reconciliation, apologetics, moderation and ambassadorial work. (This personality profile describes my ‘role’ as “diplomat”. http://www.16personalities.com/infj-personality ) Much of this blog chronicals the destruction of my former headstrong epistemolgy as it was dashed agaisnt the rocky shore of reality; and the result is an extreme aversion to most absolutes. Now I’m a lover, not a fighter.

The point of all this biographical stuff is to establish that I have close friends and family all over the spectrum. Most of you reading this do as well. But what I’ve noticed from talking to a lot of ex-conservatives, and reading comments online, is that most people do not respect those on opposing sides of their political/philosophical spectrum. I can’t claim that I respect everyone who disagrees with me. But I think the AMOUNT of disrespect I see out there is unnecessary and unhealthy for everyone. When I hear my liberal friends say that people who vote for Republicans are actually, literally evil, it hurts my feelings. I have many loved ones and friends who I know very well are not evil, and I know that when I was very conservative I was not evil. Here’s a quote in the book, (not written by the author, but used as an example of what I’m talking about.)

“Republicans don’t believe in the imagination, partly because so few of them have one, but mostly because it gets in the way of their chosen work, which is to destroy the human race and the planet. Human beings, who have imaginations, can see a recipe for disaster in the making; Republicans, whose goal in life is to profit from disaster and who don’t give a hoot about human beings, either can’t or won’t. Which is why I personally think they should be exterminated before they cause any more harm.” ~ Michael Feingold

I’ve seen this basic message from many of my liberal friends more times than I can count. The other day a friend casually mentioned how it was too bad the entire republican presidential field was “batshit insane”. After I failed to give him the expected hallelujah chorus or high five, he moderated the statement with: “I mean… not in a bad way.”

So when I found a book written by a liberal atheist that actually acknowledges the fact that conservatives are not actually mustache-twirling villains., it was very exciting to me.

Furthermore, it’s well written, well researched, and really fun to read. The only thing that bummed me out about the book is the fact that two of its central arguments involve ideas that most of my conservative Christian friends will reject. (Dealing with free will and evolution) So I don’t think this book will help much with the problem of conservatives who think liberals are evil. Though one of the elements is powerful enough that I think, even on its own, might soften some conservative hearts.

But I think the whole gist of the book really is most powerful when taken all together, and only a liberal will be able to buy in to the first several important parts. (I’m liberal enough to buy in.) This is important, because the later part of the book contains some ideas that will be very challenging for a liberal. For that reason I hope that the quotes I’m going to be putting in here don’t instantly turn off my liberal friends. I hope that they can keep an open mind long enough to check out the whole flow of the argument by reading the book, then see if what he has to say is as outrageous as they may initially find them.

The following summary is in no way a systematic one. It’s the stuff that really stuck out to me. So please don’t read this smattering of thoughts and quotes as a representation of the structure of the argument that the book makes. I hope you’ll see this as a sampler buffet of ideas that inspires you to dig deeper by reading the full book. Or, if you need, I’ll read it to you. Assuming you have enough eye drops.

I’ll start with a very rough outline of the argument. First, Haidt’s research has shown that morality is a gut instinct thing. No one sits down and rationally deduces their moral structure. Well, except for philosophers. And even they just end up doing a more complicated dance of post-hoc rationalizations than non-philosophers. Non-philosophers don’t bother dancing; they just cut straight to the post-hoc rationalizations. (For clarity: post-hoc means that it’s an argument made up after a decision has already been made, but pretending to be the explanation that was thought about before the decision had been made. It’s a very common self-deception.) Haidt and his team conducted a lot of tests over many years to discover this fact. The description of these tests is fascinating. I’ll just say that they basically show that no matter how unjustified a moral belief is, it can NOT be changed with counter-arguments. Even when participants admitted that each and every ‘reason’ they brought up was soundly rebutted by the tester-person, they still insisted that their original position was ‘right’.

Haidt makes an analogy of an elephant and rider, comparing the elephant to our emotional gut-level instincts, and the rider to our rational/conscious mind. The elephant is the one with the most power in that relationship, and the rider is mostly resigned to explaining WHY the elephant went the way it did, and how they (the rider) was actually the one directing it. Another analogy he used, that I liked better, is that of a press secretary. The president is the emotions; the press secretary is the rational mind. Our minds are experts at spinning everything the president (emotions) do. A press secretary's job is make everything the president does seem coherent, morally right and well-reasoned. So when our moral ideas are challenged we don’t step back and calmly ascertain the validity of the challenge. We don’t go to the president and interrogate them to try to get them to change their mind. Instead, our inner press secretary jumps in and starts arguing over the annoying press member who’s poking holes in the president’s plan. Neither analogy is perfect, but both illustrate that all our talk of our moral justifications are post-hoc arguments because our brains are VERY resistant to examining our fundamental moral matrices.

This idea that there’s a vast area of our self that is determined NOT by our own rational thinking is hard to swallow. Especially if you’re a conservative who finds the idea of Total Free Will to be foundational to your worldview. Fortunately, most liberals are more open to the idea that there are parts of our decision-making faculties that are heavily or totally influenced by outside factors. (Such as the idea of poverty leading to crime vs. the conservative insistence that only low moral character leads to crime. Or that military intervention flames terrorist sentiment vs. the conservative’s assumptions that terrorist do what they do because they hate our freedom.)

A very important element that comes up again and again in this book is the social dimension. When it comes to this issue of post-hoc argumentation for our gut-instincts, he says this:

“We do moral reasoning not to reconstruct the actual reasons why we ourselves came to a judgment; we reason to find the best possible reasons why somebody else ought to join us in our judgement.”

Which makes sense. If I were on a deserted island I would not spend a lot of time trying to explain my moral code to myself. He follows a couple of intellectual/philosophical threads through the millennia comparing and contrasting ideas about morality. Rather than attempt to summarize those parts I’m just going to pull some quotes that I found particularly interesting.

“The social intuitionist model offers an explanation of why moral and political arguments are so frustrating: because moral reasons are the tail wagged by the intuitive dog. A dog’s tail wags to communicate. You can’t make a dog happy by forcibly wagging its tail. And you can’t change people’s minds by utterly refuting their arguments. Hume diagnosed the problem long ago: “And as reasoning is not the source, whence either disputant derives his tenets; it is in vain to expect, that any logic, which speaks not to the affections, will ever engage him to embrace sounder principles.””

And here’s something I’ve found to be very true:

“Perkins found that IQ was by far the biggest predictor of how well people argued, but it predicted only the number of my-side arguments. Smart people make really good lawyers and press secretaries, but the are no better than others at finding reasons on the other side. “people invest their IQ in buttressing their own case rather than in exploring the entire issue more fully and evenhandedly.””

This is becoming especially problematic thanks to the internet where anyone can find any “authority” to back up any claim to bolster their my-side arguments.

“we can call up a team of supportive scientists for almost any conclusion twenty-four hours a day.”

Haidt then talks biographically about his gradual conversion from being a know-it-all to gaining some actual understanding and empathy for those who held other worldviews.

“Liberalism seemed so obviously ethical. Liberals marched for peace, worker’ rights, civil right, and secularism. The Republican Party was (as we saw it) the party of war, big business, racism, and evangelical Christianity. I could not understand how any thinking person would voluntarily embrace the party of evil, and so I and my fellow liberals looked for psychological explanations of conservatism, but not liberalism. We supported liberal policies because we saw the world clearly, and wanted to help people, but they supported conservative policies out of pure self-interest (lower my taxes!) or thinly veiled racism (stop funding welfare programs for minorities!). We never considered the possibility that there were alternative moral worlds in which reducing harm (by helping victims) and increasing fairness (by pursuing group-based equality) were not the main goals. And if we could not imagine other moralities, then we could not believe that conservatives were as sincere in their moral beliefs as we were in ours.”

“Liberalism seemed so obviously ethical. Liberals marched for peace, worker’ rights, civil right, and secularism. The Republican Party was (as we saw it) the party of war, big business, racism, and evangelical Christianity. I could not understand how any thinking person would voluntarily embrace the party of evil, and so I and my fellow liberals looked for psychological explanations of conservatism, but not liberalism. We supported liberal policies because we saw the world clearly, and wanted to help people, but they supported conservative policies out of pure self-interest (lower my taxes!) or thinly veiled racism (stop funding welfare programs for minorities!). We never considered the possibility that there were alternative moral worlds in which reducing harm (by helping victims) and increasing fairness (by pursuing group-based equality) were not the main goals. And if we could not imagine other moralities, then we could not believe that conservatives were as sincere in their moral beliefs as we were in ours.”

He goes on to talk about moving to India to study cultural psychology and living with a traditional family. Observing the daily life and moral world that was so foreign to him caused the idea of other moral matrices to impact his previous view that there’s really only one correct moral matrix: the modern secular western educated one. He was then able to parse the rhetoric from the right with a “clinical detachment” and see that the specific policies such as prayer and corporal punishment in schools, and no sex education, etc. came from a place other than a totalitarian desire to control every aspect of people’s lives. (we’ll get to what that is later.) But he then goes on to say what I hope all liberals who read this -and then the book- will end up saying.

“It felt good to be released from partisan anger. and once I was no longer angry, I was no longer committed to reaching the conclusion that righteous anger demands: we are right, and they are wrong. I was able to explore new moral matrices, each one supported by its own intellectual traditions. It felt like a kind of awakening.”

Then comes what I think is the central focus of the book and Haidt’s work. I think they sum it up on the website better than I can, so I’ll just past from there.

Moral Foundations Theory was created by a group of social and cultural psychologists (see us here) to understand why morality varies so much across cultures yet still shows so many similarities and recurrent themes. In brief, the theory proposes that several innate and universally available psychological systems are the foundations of “intuitive ethics.” Each culture then constructs virtues, narratives, and institutions on top of these foundations, thereby creating the unique moralities we see around the world, and conflicting within nations too. The five foundations for which we think the evidence is best are:

1) Care/harm: This foundation is related to our long evolution as mammals with attachment systems and an ability to feel (and dislike) the pain of others. It underlies virtues of kindness, gentleness, and nurturance.

2) Fairness/cheating: This foundation is related to the evolutionary process of reciprocal altruism. It generates ideas of justice, rights, and autonomy. [Note: In our original conception, Fairness included concerns about equality, which are more strongly endorsed by political liberals. However, as we reformulated the theory in 2011 based on new data, we emphasize proportionality, which is endorsed by everyone, but is more strongly endorsed by conservatives]

3) Loyalty/betrayal: This foundation is related to our long history as tribal creatures able to form shifting coalitions. It underlies virtues of patriotism and self-sacrifice for the group. It is active anytime people feel that it's "one for all, and all for one."

4) Authority/subversion: This foundation was shaped by our long primate history of hierarchical social interactions. It underlies virtues of leadership and followership, including deference to legitimate authority and respect for traditions.

5) Sanctity/degradation: This foundation was shaped by the psychology of disgust and contamination. It underlies religious notions of striving to live in an elevated, less carnal, more noble way. It underlies the widespread idea that the body is a temple which can be desecrated by immoral activities and contaminants (an idea not unique to religious traditions).

We think there are several other very good candidates for "foundationhood," especially:

6) Liberty/oppression: This foundation is about the feelings of reactance and resentment people feel toward those who dominate them and restrict their liberty. Its intuitions are often in tension with those of the authority foundation. The hatred of bullies and dominators motivates people to come together, in solidarity, to oppose or take down the oppressor. We report some preliminary work on this potential foundation in this paper, on the psychology of libertarianism and liberty.

Much of our present research involves applying the theory to political "cultures" such as those of liberals and conservatives. The current American culture war, we have found, can be seen as arising from the fact that liberals try to create a morality relying primarily on the Care/harm foundation, with additional support from the Fairness/cheating and Liberty/oppression foundations. Conservatives, especially religious conservatives, use all six foundations, including Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Sanctity/degradation. The culture war in the 1990s and early 2000s centered on the legitimacy of these latter three foundations. In 2009, with the rise of the Tea Party, the culture war shifted away from social issues such as abortion and homosexuality, and became more about differing conceptions of fairness (equality vs. proportionality) and liberty (is government the oppressor or defender?). The Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street are both populist movements that talk a great deal about fairness and liberty, but in very different ways

________________________________________

So given this variety of foundations upon which to build a moral platform it’s no wonder that we have such a large variety of moral platforms. One of the coolest things Haidt has done is to design a website that helps his team gather data on people and their beliefs so that he can build testable models of this. ( http://www.yourmorals.org/ )

And here’s some of the neat charts he’s made.

So you can see that the more liberal you are the more you value Care and Fairness above everything else. Whereas conservatives mix in Loyalty, Authority and Sanctity. You can see in the second chart that those who identify as “Very conservative” even put Authority, Sanctity and Loyalty ABOVE Care and Fairness. This, I think, is the the central reason that liberals perceive that conservatives are evil. Not only do liberals prioritize Care and Fairness, but the more liberal you are, the more likely you are to strongly reject Loyalty Authority and Sanctity AS legitimate moral foundations. As a friend of mine put it in a facebook conversation we were having about this subject: “Conservatives tend to place a lot of importance on things for which I have no use, whose absence I do not miss, and whose absence generally makes my life more enjoyable (importance of vaguely defined but dogmatically acclaimed virtues like faith, adherence to norms in general, categorized & prescribed roles in human interaction, systematized social constructs, hierarchical relationships, etc). As such, I suspect that I would not be convinced by the perceived "necessity" or "importance" of their additional moral categories.“

Here is an example of three moral matrices and the weight distribution that each places on the moral foundations:

As you can see, the conservative moral matrix is the most balanced. But any liberal will point out that it’s only because they are putting weight on three illegitimate foundations! They are pulling weight AWAY from Care and Fairness (Indicated by how thick the lines are) in order to bolster repressive evil terrible ideas like blind obedience, sexual repression and jingoism. This is where things get interesting. Haidt spills a LOT of ink delving into the evolutionary reasons why these three troublesome-for-liberals foundations may have come about. And even more challenging… why they may still be necessary for a functioning society. Not in the sense that they ought to overpower Care and Fairness; but more that they are a necessary yang to the liberal yin. I’m going to come back to this later.

Next Haidt talks about WHY those three questionable-to-liberal moral foundations (And the others as well) exist from an evolutionary perspective. He states up front that there’s an annoying trend in academia to back up one’s position by cherry picking evolution for sloppy theories that support their argument. And I think he does an admirable job avoiding that pitfall. His argument does not boil down to “Our monkey ancestors had to form hierarchies so we should to lol!”. I really enjoyed this part of the book where he builds a case for how and why our brains evolved the way they did, why group evolution was an important driver, and how that evolutionary psychology and sociology created the foundations that he has been postulating and researching. I’m not going to summarize this part either. Just take my word for it that it’s great, and buy the book.

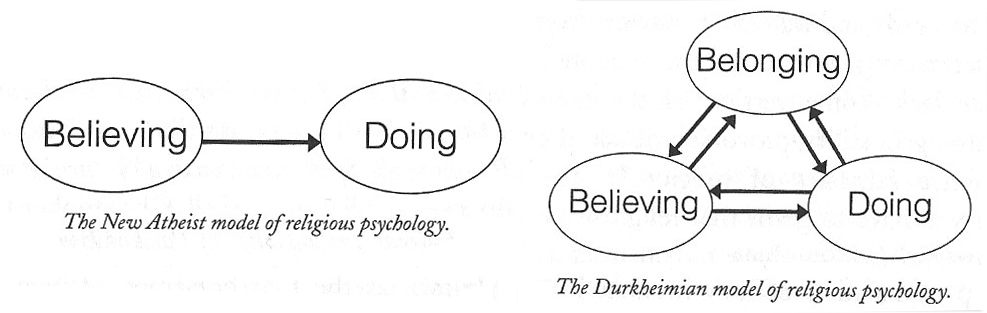

Next up is some talk about the New Atheists’ part in the western culture wars. I was surprised to read some ideas that I’ve FELT all my life, but never seen articulated about my religious upbringing. He basically says that the New Atheists have a fundamental misunderstanding about what religion IS. Their critique of religion stems from the faulty idea that he illustrates with the diagram below, on the left. He shows that it’s actually like the one on the right.

He says they spin their wheels attacking religious belief, because they think if the religious person will find find out their beliefs are wrong then they will do different things. (“Oh, I WON’T get 72 virgins in heaven if I suicide bomb? I guess I won’t then.”) But as Haidt established near the beginning of the book: human beliefs don’t come from rational thought, nor can they be changed with rational argument. And his insight into the community aspect of morality explains why. What we humans do, believe, and who we hang out with are all a web of interdependencies and gird each other. The reason it’s SO difficult to change a person’s moral, religious, or philosophical beliefs is because they are embedded in so much other life stuff that would be undone by that change. The human brain is very good at conserving energy, and it knows damn well what the repercussions of ripping oneself out of a community of like-minded, supporting people who love and respect you would be. Just ask any ex-religious atheist about the process.

“Supernatural agents do of course play a central role in religion, just as the actual football is at the center of the whirl of activity on game day... But trying to understand the persistence and passion of religion by studying beliefs about God is like trying to understand the persistence and passion of ... football by studying the movements of the ball. You’ve got to broaden the inquiry. You've got to look at the ways that religious beliefs work with religious practices to create a religious community.”

OK, back to politics and morality. The last third of the book contains the challenging stuff about why those evil conservatives think stupid stuff like sanctity, loyalty and authority are important enough to draw energy and resources away from the ACTUAL moral stuff like care and fairness.

Here’s one quote that particularly caught my attention.

“We can look more closely at people’s strong desires to protect their communities from cheaters, slackers and free riders, who, if allowed to continue their ways without harassment, would cause others to stop cooperating, which would cause society to unravel.”

This, I presume, is a statement that contains premises which most liberals would disagree with. First of all, it has the flavor of a Chicken Little about it. But then Haidt brings up a fascinating study that looked at communes in the 1800s. (Of which there were a surprisingly large amount.) It compared and contrasted secular and religious communes. Being a microcosm of society, they provide interesting little blips of social engineering that can give us a glimpse at the effects of particular ideologies. It turns out that religious communes lasted way, way longer than secular ones. And surprisingly, the more strict the religious sect, the longer it lasted.

“Why doesn’t sacrifice strengthen secular communes? Sosis argues that rituals, laws, and other constraints work best when they are sacralized. He quotes the anthropologist Roy Rappaport: “To invest social conventions with sanctity is to hide their arbitrariness in a cloak of seeming necessity.” But when secular organizations demand sacrifice, every member has a right to ask for a cost-benefit analysis, and many refuse to do things that don’t make logical sense. In other words, the very ritual practices that the New Atheists dismiss as costly, inefficient, and irrational turn out to be a solution to one of the hardest problems humans face: cooperation without kinship. Irrational beliefs can sometimes help the group function more rationally, particularly when those beliefs rest upon the Sanctity foundation. Sacredness binds people together, and then blinds them to the arbitrariness of the practice.”

This reminds me of my favorite line from The Hogfather, that speaks to the need for belief in what does not exist in order to make it exist.

“All right," said Susan. "I'm not stupid. You're saying humans need...fantasies to make life bearable."

REALLY? AS IF IT WAS SOME KIND OF PINK PILL? NO. HUMANS NEED FANTASY TO BE HUMAN. TO BE THE PLACE WHERE THE FALLING ANGEL MEETS THE RISING APE.

"Tooth fairies? Hogfathers? Little—"

YES. AS PRACTICE. YOU HAVE TO START OUT LEARNING TO BELIEVE THE LITTLE LIES.

"So we can believe the big ones?"

YES. JUSTICE. MERCY. DUTY. THAT SORT OF THING.

"They're not the same at all!"

YOU THINK SO? THEN TAKE THE UNIVERSE AND GRIND IT DOWN TO THE FINEST POWDER AND SIEVE IT THROUGH THE FINEST SIEVE AND THEN SHOW ME ONE ATOM OF JUSTICE, ONE MOLECULE OF MERCY. AND YET—Death waved a hand. AND YET YOU ACT AS IF THERE IS SOME IDEAL ORDER IN THE WORLD, AS IF THERE IS SOME...SOME RIGHTNESS IN THE UNIVERSE BY WHICH IT MAY BE JUDGED.

"Yes, but people have got to believe that, or what's the point—"

MY POINT EXACTLY.”

I think that liberals assume too much when they assume that if a society drops the ‘ugly three’ foundations, that new ways to address the age-old problem of fostering cooperation without kinship will automatically emerge. In fact, I don’t think they even know such a problem exists because we live in a such a comfortable and stable society right now. If every human always did a cost/benefit analysis of every action before deciding to contribute to the social good then I think there’s a good chance that everything falls apart. We need the sacred in order to ease the sacrifices that we have to make for the common good. Sacredness is not a thing that exists on it’s own. Like language, it’s a shared human consensus about a thing. That means it’s fragile if the consensus erodes. More on that in a minute...

“We evolved to live, trade, and trust within shared moral matrices. When societies lose their grip on individuals, allowing all to do as they please, the result is often a decrease in happiness and in increase in suicide, as Durkheim showed more than a hundred years ago. Societies that forgo the exoskeleton of religion should reflect carefully on what will happen to them over several generations. We don’t really know, because the first atheistic societies have only emerged in Europe in the last few decades. They are the least efficient societies ever known at turning resources (of which they have a lot) into offspring (of which they have few)”.

Granted, turning resources into offspring is not a high priority on a planet of 7 billion. But we are certainly running into problems with our current quality-of-life expectations with so few replacements to keep our social welfare nets intact. But that’s a can of worms I won’t go into here. The point is that we really don’t know the cost of abandoning the 3 foundations liberals dismissed so cavalierly.

Ideally, you would have read the rest of the book before you finally get to Haidt’s definition of morality, but I think it’s important to comment on it for the sake of clarity.

“Moral systems are interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, technologies and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate self-interest and make cooperative societies possible.”

Another liberal objection would be that they find the the idea of suppressing people’s desires to be authoritarian, unhealthy and evil. “I’m basically a good person. I wouldn’t hurt people. I don’t need to be told to suppress my urges!” It’s very hard for us to see the invisible forces that makes up a social moral matrix and the pressure it applies to ourselves and others. And without seeing it directly, we liberals may have lost sight of its necessity. The idea that people are essentially selfish and won’t spend resources helping those who aren’t kin is almost unthinkable to many liberals. Sure, they’ll admit this is the case for rich people and republicans, but they tend to think that the normal human beings are full of compassion and love by nature. I think the Tragedy of the Commons illustrates that this is not reality.

Haidt argues that Sanctity, Authority and Loyalty are actually a large part of the reason that society can function at all.

Another interesting study he brings up illustrates something I’ve always wondered about, because I’ve noticed that this phenomenon seemed to be the case, but I assumed it was just my bias from being half-conservative/formerly full-conservative.

“In a study I did with Jesse Graham and Brian Nosek, we tested how well liberals and conservatives could understand each other. We asked more than two thousand American visitors to fill out the Moral Foundations Questionnaire. One-third of the time they were asked to fill it out normally, answering as themselves. One-third of the time they were asked to fill it out as they think a “typical liberal” would respond. One-third of the time they were asked to fill it out as a “typical conservative” would respond. This design allowed us to examine the stereotypes that each side held about the other. More important, it allowed us to assess how accurate they were by comparing people’s expectations about “typical” partisans to the actual responses from partisans on the left and the right. Who was best able to pretend to be the other?

The results were clear and consistent. Moderates and conservatives were most accurate in the predictions, whether they were pretending to be liberals or conservatives. Liberals were the least accurate, especially those who described themselves as “very liberal.” The biggest errors in the whole study came when liberals answered the Care and Fairness questions while pretending to be conservatives. When faced with question such as “One of the worst things a person could do is hurt a defenseless animal” or “Justice is the most important requirement for society,” liberals assumed that conservatives would disagree. If you have a moral matrix built primarily on intuitions about care and fairness (as equality), and you listen to the Reagan narrative, what else could you think? Reagan seems completely unconcerned about the welfare of drug addicts, poor people, and gay people. He’s more interested in fighting wars and telling people how to run their sex lives.

If you don’t see that Reagan is pursuing positive values of Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity, you almost have to conclude that Republicans see no positive value in Care and Fairness.”

So again. I think liberals confuse the conservative attempt to balance care and fairness with other values as an active attack on care and fairness. And this leads them to see the mustache twirling villains.

Haidt talks about his first time reading about conservatism in a way that made sense to him, in historian Jerry Muller’s book: Conservatism. I tried to sum this up, but found that the whole arc of the story is vital to understanding the key that I hope liberals will find to unlocking their hearts and minds to be more loving and understanding towards conservatives. So I just typed out several pages from the book. That’s probably immoral and illegal. Sorry. But you know… I’m half conservative… so…

“Muller began by distinguishing conservatism from orthodoxy. Orthodoxy is the view that there exists a “transcendent moral order, to which we ought to try to conform the ways of society.” Christians who look to the Bible as a guide for legislation, like Muslims who want to live under sharia, are examples of orthodoxy. They want their society to match an externally ordained moral order, so they advocate change, sometimes radical change. This can put them at odds with true conservatives, who see radical change as dangerous.”

“Muller began by distinguishing conservatism from orthodoxy. Orthodoxy is the view that there exists a “transcendent moral order, to which we ought to try to conform the ways of society.” Christians who look to the Bible as a guide for legislation, like Muslims who want to live under sharia, are examples of orthodoxy. They want their society to match an externally ordained moral order, so they advocate change, sometimes radical change. This can put them at odds with true conservatives, who see radical change as dangerous.”

Muller next distinguished conservatism from the counter-Enlightenment. It is true that most resistance to the Enlightenment can be said to have been conservative, by definition (i.e., clerics and aristocrats were trying to conserve the old order). But modern conservatism, Muller asserts, finds its origins within the main currents of Enlightenment thinking, when men such as David Hume and Edmund Burke tried to develop a reasoned, pragmatic, and essentially utilitarian critique of the Enlightenment project. Here’s the line that quite literally floored me:

“What makes social and political arguments conservative as opposed to orthodox is that the critique of liberal or progressive arguments takes place on the enlightened grounds of the search for human happiness based on the use of reason.”

As a lifelong liberal, I had assumed that conservatism = orthodoxy = religion = faith = rejection of science.

It followed, therefore, that as an atheist and scientist, I was obligated to be a liberal. But Muller asserted that modern conservatism is really about creating the best possible society, the one that brings about the greatest happiness given local circumstances. Could it be? Was there a kind of conservatism that could compete against liberalism in the court of social science? Might conservatives have a better formula for how to create a healthy, happy society?

I kept reading. Muller went through a series of claims about human nature and institutions, which he said are the core beliefs of conservatism. Conservatives believe that people are inherently imperfect and are prone to act badly when all constraints and accountability are removed (yes, I thought; see Glaucon, Tetlock, and Ariely in chapter 4). Our reasoning is flawed and prone to overconfidence, so it’s dangerous to construct theories based on pure reason, unconstrained by intuition and historical experience (yes; see Hume in chapter 2 and Baron-Cohen on systematizing in chapter 6). Institutions emerge gradually as social facts, which we then respect and even sacralize, but if we strip these institutions of authority and treat them as arbitrary contrivances that exist only for our benefit, we render them less effective. We then expose ourselves to increased anomie and social disorder (yes; see Durkheim in chapters 8 and 11).

Based on my own research, I had no choice but to agree with these conservative claims. As I continued to read the writings of conservative intellectuals, from Edmund Burke in the eighteenth century through Friedrich Hayek and Thomas Sowell in the twentieth, I began to see that they had attained a crucial insight into the sociology of morality that I had never encountered before. They understood the importance of what I’ll call moral capital. (Please not that I am praising conservative intellectuals, not the Republican Party.)

The term social capital swept through the social sciences in the 1990s, jumping into the broader public vocabulary after Robert Putnam’s 2000 book Bowling Alone. Capital, in economics, refers to the resources that allow a person or firm to produce goods or services. There’s financial capital (money in the bank), physical capital (such as a wrench or a factory), and human capital (such as a well-trained sales force). When everything else is equal, a firm with more of any kind of capital will outcompete a firm with less.

Social capital refers to a kind of capital that economists had largely overlooked: the social ties among individuals and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from those ties. When everything else is equal, a firm with more social capital will outcompete its less cohesive and less internally trusting competitors (which makes sense given that human beings were shaped by multilevel selection to be contingent cooperators). In fact, discussions of social capital sometimes use the example of ultra-Orthodox Jewish diamond merchants, which I mentioned in the previous chapter. This tightly knit ethnic group has been able to create the most efficient market because their transaction and monitoring costs are so low- because there’s less overhead on every deal. And their costs are so low because they trust each other. If a rival market were to open up across town composed of ethnically and religiously diverse merchants, they’d have to spend a lot more money on lawyers and security guards, given how easy it is to commit fraud or theft when sending diamonds out for inspection by other merchants. Like the nonreligious communes studied by Richard Sosis, they’d have a much harder time getting individuals to follow the moral norms of the community.

Everyone loves social capital. Whether you’re left, right, or center, who could fail to see the value of being able to trust and rely upon others? But now let’s broaden our focus beyond firms trying to produce goods and let’s think about a school, a commune, a corporation, or even a whole nation that wants to improve moral behavior. Let’s set aside problems of moral diversity and just specify the goal as increasing the “output” of behaviors, however the group defines those terms. To achieve almost any moral vision, you’d probably want high levels of social capital. (It’s hard to imagine how anomie and distrust could be beneficial.) But will linking people together into healthy, trusting relationships be enough to improve the ethical profile of the group?

If you believe that people are inherently good, and that they flourish when constraints and division are removed, then yes, that may be sufficient. But conservatives generally take a very different view of human nature. They believe that people need external structure or constraints in order to behave well, cooperate, and thrive. These external constraints include laws, institutions, customs, traditions, nations, and religions. People who hold this “constrained” view are therefore very concerned about the health and integrity of these “outside-the-mind” coordination devices. Without them, they believe, people will begin to cheat and behave selfishly. Without them, social capital will rapidly decay.

If you are a member of a WEIRD society, [Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic] your eyes tend to fall on individual objects such as people, and you don’t automatically see the relationships among them. Having a concept such as social capital is helpful because it forces you to see the relationships within which those people are embedded, and which make those people more productive. I propose that we take this approach one step further. To understand the miracle of moral communities that grow beyond the bounds of kinship we must look not just at people, and not just at the relationships among people, but at the complete environment within which those relationships are embedded, and which makes those people more virtuous (however they themselves define that term). It takes a great deal of outside-the-mind stuff to support a moral community.

For example, on a small island or in a small town, you typically don’t need to lock your bicycle, but in a big city in the same country, if you only lock the bike frame, your wheels may get stolen.

Being small, isolated, or morally homogeneous are examples of environmental conditions that increase the moral capital of a community. That doesn’t mean that small islands and small towns are better places to live overall - the diversity and crowding of big cities makes them more creative and interesting places for many people - but that’s the trade-off. (Whether you’d trade away some moral capital to gain some diversity and creativity will depend in part on your brain’s settings on the traits such as openness to experience and threat sensitivity, and this is part of the reason why cities are usually so much more liberal than the countryside.)

Looking at a bunch of outside-the-mind factors and at how well they mesh with inside-the-mind moral psychology brings us right back to the definition of moral systems that I gave in the last chapter. In fact, we can define moral capital as the resources that sustain a moral community. More specifically, moral capital refers to:

the degree to which a community possesses interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, and technologies that mesh well with evolved psychological mechanisms and thereby enable the community to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperation possible.

To see moral capital in action, let’s do a thought experiment using the nineteenth-century communes studied by Richard Sosis. Let’s assume that every commune was started by a group of twenty-five adults who knew, liked, and trusted one another. In other words, let’s assume that every commune started with a high and equal quantity of social capital on day one. What factors enabled some communes to maintain their social capital and generate high levels of prosocial behavior for decades while others degenerated into discord and distrust within the first year?

In the last chapter, I said that belief in gods and costly religious rituals turned out to be crucial ingredients of success. But let’s put religion aside and look at other kinds of outside-the-mind stuff. Let’s assume that each commune started off with a clear list of values and virtues that it printed on posters and displayed through the commune. A commune that valued self-expression over conformity and that prized the virtue of tolerance over the virtue of loyalty might be more attractive to outsiders, and this could indeed be an advantage in recruiting new members, but it would have lower moral capital than a commune that valued conformity and loyalty. The stricter commune would be better able to suppress or regulate selfishness, and would therefore be more likely to endure.

Moral communities are fragile things, hard to build and easy to destroy. When we think about very large communities such as nations, the challenge is extraordinary and the threat of moral entropy is intense. There is not a big margin for error; many nations are failures as moral communities, particularly corrupt nations where dictators and elites run the country for their own benefit. If you don’t value moral capital, then you won’t foster values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, and technologies that increase it.

Let me state clearly that moral capital is not always an unalloyed good. Moral capital leads automatically to the suppression of free riders, but it does not lead automatically to other forms of fairness such as equality of opportunity. And while high moral capital helps a community to function efficiently, the community can use that efficiency to inflict harm on other communities. High moral capital can be obtained within a cult or fascist nation, as long as most people truly accept the prevailing moral matrix.

Nonetheless, if you are trying to change an organization or a society and you do not consider the effects of your changes on moral capital, you’re asking for trouble. This, I believe, is the fundamental blind spot of the left. It explains why liberal reforms so often backfire, and why communist revolutions usually end up in despotism. It is the reason I believe that liberalism -which has done so much to bring about freedom and equal opportunity- is not sufficient as a governing philosophy. It tends to overreach, change too many things too quickly, and reduce the stock of moral capital inadvertently. Conversely, while conservatives do a better job of preserving moral capital, they often fail to notice certain classes of victims, fail to limit the predations of certain powerful interests, and fail to see the need to change or update institutions as times change.”

Whew! That was a really long quote. So here’s a picture of Iron Man punching Captain America.

The question I’ve never heard a liberal ask is this: “Are the progressive net positives that liberalism bring ever offset by any negatives?” I’ve found that the assumption (because I make it myself) is generally that liberal policy and personality is ONLY sunshine and light. Because it FEELS right. It feels LOVING. Giving grace to the underprivileged, accepting the weirdos, (As long as they aren’t the intolerant bigoted weirdos.) standing up to bullies, and helping the needy in every way we can. It’s not immediately obvious that doing these things could POSSIBLY have a downside. But conservatives see it. They FEEL social capital in a way that liberals don’t. And they sense when those load-bearing beams are cracking. I think they tend to care about that structure too much, to the point that they will allow for more suffering than is needed occur to keep those buttresses firm.

But they honestly feel like it’s for the good of all. I know this because they sacrifice THEMSELVES for it.

““When political scientists looked into it, they found that self-interest does a remarkably poor job of predicting political attitudes.”

Liberals misinterpret the conservative poor as being dupes for big business and the religious right. “Don’t they know they’d be better off (get more social services) if they voted democrat?!” But the conservative poor know that. They believe that they are ‘taking one for the team’. In their minds they are nobly sacrificing their welfare for that of society by voting for those that say they are upholding those 3 moral foundations that liberals reject, but that the conservative poor believe are vital. Because they are convinced that without those moral values being held up society will start to unravel.

I’m guessing this is where the conservative attitude comes from where they see liberals as hippies who only care about feelings and not results, and themselves as the practical grown-ups who have to keep society from falling apart.

So I agree with Haidt that social capital is both a real, important thing, and a liberal blind spot. And I think the conservative blindspot is related, and just as bad. Whenever I post anything about social justice I get a very regular response from conservatives. They can be summed up like this: “Racism/sexism/etc was an issue 30 years ago but doesn’t affect anyone these days.” They are completely blind to institutional forms of oppression that make the daily lives of many much more difficult than others. Again, it gets back to the individual-interpersonal levels of society. It’s much easier to focus on one person at a time. To lay praise and blame on a person, and not have to account for the near-infinite influences that shape their decisions, freedoms, emotional and intellectual resources. That’s really damn complicated, and if you go too far into the woods you lose all sense of accountability. I understand that fear. I agree with the reasoning behind that fear. Not because I’m a staunch believer in total free will. (quite the opposite in fact.) But because the BELIEF in one’s own power to shape their own destiny is paramount to making the most you can out of your situation in life. Unlike the conservative, I don’t push that idea to the extreme where I then say that anyone -no matter their starting point- can achieve anything if they work hard enough. But if you preach the bad news of societal inequality you can inadvertently make things worse for those who already have the short end of the stick by discouraging them to the point where they think the only way they can succeed is if the government steps in a fixes the broken systems.

As a half conservative / half liberal I can’t be trusted by either side. I’m a weak-willed sellout who caved to the pressure of my liberal peers in the eyes of conservatives. And I have conservative baggage that I can’t dump in the eyes of liberals. That’s one of the reasons I don’t bother to chime in on overtly political topics. (I don’t count social issues even though they always have political ties.)

But since Haidt is an atheist liberal, he can speak powerfully to you folks on the left side of the spectrum. I’ll keep my eyes peeled for a counterpart on the other end.

“Morality binds and blinds. This is not just something that happens to people on the other side. We all get sucked into tribal moral communities. We circle around sacred values and then share post hoc arguments about why we are so right and they are so wrong. We think the other side is blind to truth, reason, science, and common sense, but in fact everyone goes blind when talking about their sacred objects.

If you want to understand another group, follow the sacredness. As a first step, think about the six moral foundations, and try to figure out which one or two are carrying the most weight in a particular controversy. And if you really want to open your mind, open your heart first. If you can have at least one friendly interaction with a member of the “other” group, you’ll find it far easier to listen to what they’re saying, and maybe even see a controversial issue in a new light. You may not agree, but you’ll probably shift from Manichaean disagreement to a more respectful and constructive yin-yang disagreement.”

This book was very eye-opening for me and brought me several epiphanies. Such as:

I learned why I’m so liberal.

My personality profile is such that I do not naturally see the 3 conservative moral foundations of Authority, Loyalty and Sacredness as worthy of balance with the two major liberal ones of care and fairness. I can still see why they are important. (See this very Authority/Sanctity oriented ceremony I designed for my sons: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1WOZx1TYuqE ) But they are SO EASILY to corrupted by terrible people to control and abuse others. Like… Loyalty? I GUESS that’s a virtue. But only so far as the person/organization is WORTHY of it. People and organizations can and do change. So being loyal can easily make you compromise your values if Loyalty is way up there in your priorities. I know that I wouldn’t want someone to be unquestioningly loyal to me. I want people to rally to my aid IF I DESERVE it, not out of some weird sycophantic brain wrinkle. Same with Authority, same with patriotism, same with tradition. So while I think I understand Haidt’s arguments about why and how they keep social capital around, I don’t intuitively FEEL it.

But besides seeing why I’m so liberal, I also see why I’m so conservative.

Because I know that I don’t know enough to be sure that radical liberal societal changes won’t have unforeseen devastating consequences that could harm more than they help. It’s nice to think that all the conservative stuff that societies have that don’t FEEL loving… stuff like hierarchy, zealotry, jingoism, etc. are simply harmful backward baggage that can be tossed aside like an old snake skin. But I have a dimmer view of human nature than many liberals seem to. I think our natural state is red in tooth and claw. So very powerful external forces are still necessary to keep us from that state being the norm. And even though I’m not passionate about authority, loyalty and sacredness, I can see how they are probably the things that keep us from Armageddon.

While I agree with liberals that much of human tradition and institutions came about through processes of the powerful preying on the less-powerful, I also agree with the conservatives that those systems keep society stable and cooperative. It’d be great to be able to scientifically experiment with societies by radically altering them according to every liberal ideal to see what would happen. But I think what would happen is economic collapse, disaster, famine, chaos and ultimately more war than we have already. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe a pure socialist or communist or anarchist society could work on a large scale. Maybe the reason it hasn’t worked yet is because those ‘experiments’ were all watered down with bits of capitalism, religion, or whatever other ‘impurities’ might mess up the perfect society. But since we can’t do laboratory experiments with hundreds of millions of people at once, we are stuck with the politics we know. Politicians. pundits, financial interests, etc. all in a tangled tug of war. And given that reality, MY opinion is that it’s good that we are mostly gridlocked. One foot stuck in the past and one straining into a new, unknown social construct.

But this book isn’t really about politics per se. It’s about how we regard the ‘other’ in our daily lives. It’s how we tend to dehumanize and demonize those who believe differently than we do. I really don’t care who you vote for or what party you support. I care that you hate. That you loathe, condemn and insult people who probably don’t deserve it. Not for them. For you. Life is so much better when you don’t hate half the population of your country. I mean… I’d be NICE if I didn’t get the message that my parents are racist hateful idiots for how they vote. But let’s not make this about me.

IF you truly want the best for this world, you want consensus. Consensus does not come about by telling everyone who disagrees with you that they are evil. It really doesn't matter that some percentage of those who disagree with you really ARE evil. What matters is that reasonable people dig in hard when they are insulted. Liberal or conservative: no one reads a comment like “Only an idiot would vote for this person.” or “How evil do you have to be to believe this?” and say to themselves: “You know what? That’s a great point. Mind blown. I’ve changed completely now!” So while it might feel good to lambaste the “others” to your friends in your social network echo chamber, I think you are actually hurting yourself in two ways. First, you’re dwelling in hate or -at the very least- negativity. And second, you’re KEEPING YOUR SIDE FROM BEING HEARD. Your short-term gain of feeling like you’re part of the “good guys” is actually keeping the “good guys” from being effective. It’s like a superhero team who spends all day giving each other super high fives instead of helping anyone.

Please consider this. Your group is already motivated and activated. In order to form a greater consensus, and thus progress your agenda, you have to convince some portion of the mushy middle that your side is right and good. Every time you say that the other side is evil or stupid you are either A: directly insulting them for having believed that way to some extent, or B: directly insulting someone they love and respect. You think THAT is going to help your cause?

So how do you reach the mushy middle? Haidt puts it this way:

“Intuitions can be shaped by reasoning, especially when reasons are embedded in a friendly conversation or an emotionally compelling novel, movie, or news story.”

That quote reinforces what I take to be my calling in life, which I currently phrase: “Make the world more loving with stories.”

That’s why this book means so much to me. Haidt clearly has a similar personality profile to mine. Ambassadors. We want to facilitate healthy relationships, cultivate respect for others, and ultimately make the world a more loving place. I think that’s something both ‘sides’ can agree with.

Comments

"If every human always did a cost/benefit analysis of every action before deciding to contribute to the social good then I think there’s a good chance that everything falls apart. We need the sacred in order to ease the sacrifices that we have to make for the common good."

Making sacrifices for the common good stems from compassion and empathy - in other words, Care, not Sanctitiy. My cc. I may he misunderstanding your point here...

I value compassion above all, which is why my care game is strong. I really put considerable effort into trying to understand the relevance of Sanctity here but ultimately failed.

The part about morals and post-hoc rationalization is great btw. I'll be thinking about that a lot.

All that to say: yes, you're impulse to rise above a cost/benefit analysis of action can be seen as coming from Care rather than Sanctity. The reason I would go with Sanctity is because I think that concept is the framework within which Care exists. I'd be interested in your further thoughts on this.

I had, so far, seen empathy (and by extension compassion) as an expression of either of two things.

A - If another person is healthy and happy, and I "feel with" them (as opposed to simply observing), I am more likely to imitate whatever they were doing. If another person is in pain and I "feel with" them, I am more likely to avoid whatever I think led to them being in pain (e.g. eating something poisonous). Compassion might simply have given some of our ancestors an edge in having a healthier, longer life and producing more offspring.

B- Humans are herd animals (and interdependent), and the every individual is safest and healthiest if the heard is safest and healthiest. Compassion forges a social bond between two members of the group and helps avoiding conflict, which is beneficial for the group and consequently beneficial for the individual.

Either way, I've so far seen compassion as a logical consequence of way that humankind and society have evolved.

I am trying out right now how it feels to call it sanctity, but it feels a little like rationalizing something after the fact. And maybe that is all that morals are - an after-the-fact sacrilizing of something that has helped us survive a little longer in the past. It wouldn't surprise me. To be honest, I think on a small scale humans do that all the time - "sacrilizing" things that make us feel good: from love to soul food to money to having pets to showing around baby photos to art, we like to declare things to be above anybody's judgement.

If my compassion-based reasoning and sanctity-based reasoning led to two different conclusions, which one would I pick? I think my natural instinct would be to go with compassion in most cases. I admit that it's hard to argue that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. I hope I never have to make a decision like that in a critical situation.

You're giving me lots to think about here.

Personally, I think ALL actions that ALL people do in (regardless of worldview or religion or atheism) are primarily motivated at their base by self-interest. We are just fantastic at dressing up those motives with layers upon layers of post-hoc rationalizations to make us look more sympathetic to others and ourselves.

" It seems like the core of what you're suggesting though is that some shared framework of ideals is key to holding a society together"

That's right. That's the "social capitol" he refers to. And I think it's true that we can't continue to ground that in any kind of religious doctrine since our multicultural world is destroying all those formerly hegemonic walls. This requires a new medium for transmission, and I'm not sure what that will be. Right now the leading candidate is the news/entertainment complex. Which sucks, because it's so controlled by commercial interests.